KGB Vol 5: May 2021 PERSONAL HEALTH

AN ALTERNATE PERSPECTIVE ON GROIN HEALTH

10,00 ft view: Groin injuries are one of the most common causes of missed competition in the game of hockey.

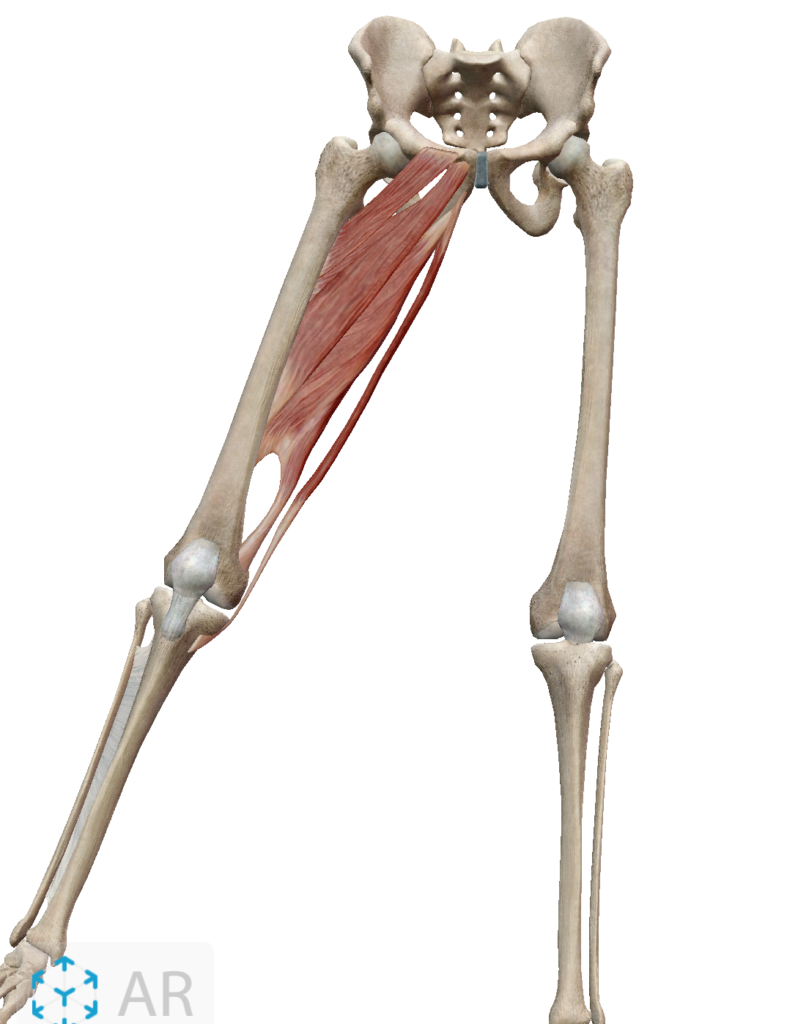

It is widely accepted that the most common cause of groin injuries is the extreme length of a player’s stride and the stress that puts on the soft-tissues. Many times a groin injury will be painful during this phase of skating, but it will also be painful with quick movements and changes of direction; even shooting and taking body contact can be bothersome. Like each player, the injury presentation is unique. The intent is to understand the true mechanism of injury and try to appreciate if we can reduce the frequency of occurrence. In this tissue-length mindset, the groin muscles would act as a breaking mechanism for the pushing power of the leg and hip. While this makes sense from a biomechanical perspective, it is controversial. When was the last time you saw a player go out with a groin strain while sprinting after a puck on a breakaway? The term for this type of stress on the muscle is “eccentric,” or a more fancy term would be “tensile” stress. There are several types of muscle or tendon injuries that occur and differential diagnosis from a trained professional is essential. The type of injury we will discuss and the lens through which we will examine tissue prep is groin injuries that occur near the insertion of the tendon into the bone commonly called “sports hernia,” “core muscle injury,” “athletic pubalgia,” or any of several other common terms.

My experience with this injury is both as a teammate of players who suffered from this issue, but more importantly from the perspective of a practitioner who treats this injury on a very frequent basis. I have always questioned the concept of eccentric overload in these injuries. This skepticism has led me to spend way too much time learning about tendons and insertional site injuries known as “enthesopathic tendinopathies.” This is pretty much a fancy term for tendon pain that is generated from the point at which that tendon inserts into the bone. We are looking specifically at changes in the bone/tendon where the groin inserts. A 2008 study 1 compared the bone swelling in 16 athletes diagnosed with osteitis pubis (8 who had surgery in this area and 8 treated conservatively) to 20 athletes (hockey/soccer) who had no symptoms in the groin. “In the nonoperative group, 4 patients (50%) still had disabling symptoms after 1 year of follow-up, and they discontinued their elite sports to a lower level during the next 3 years of follow-up. The other 4 patients in the nonoperative group continued their elite-level sports and physical therapy irregularly. Two of them returned to sports after 1 year of nonoperative treatment and 2 after 1.5 years. Their groin pain was diminished so much that they did not want to consider surgery.” The MRI results showed that the non-symptomatic athletes showed significant signs of bone swelling at the point where the groin inserts into the pelvis. This study would raise two major concerns: 1) Advanced imaging needs clinical correlation as there were plenty of MRI findings in non symptomatic athletes, and 2) Training hard, just like high-level competition, can be hard on the body. The MRIs in this study were performed in December, midseason for most hockey players and an active training environment for soccer players. Studies like this should make performance coaches take notice and heed this warning: Taking time to rest and recover in the off-season is crucial. While greater levels of swelling definitely indicated advanced tissue degeneration, the similarities in athletes without symptoms to athletes suffering with pain or a history of surgical intervention is interesting to consider.

A deeper examination of these injuries would uncover that they are not actually susceptible to stretching or eccentric stress but are more vulnerable in positions of extreme contraction also known as “compressive” force. This would seriously call into question the assumption of injury from the skating stride and force us to look at the moments when the groin muscles contract very hard from a shortened position. These moments in the game happen during the two-foot glide, change of direction, battle for position/body contact, and shooting. It is in these scenarios that the concentric or contractile force of the muscle on the tendon leads to overloading where it inserts into the bone. Given that all of these moves are critical to the sport, how can we be better and avoid injury?

Understanding how these tissues respond to loading means that we need to create an environment in training and rehab that exposes them to the same stress. Finding ways to really shorten these tissues in multiple planes of motion is where the solution will lie. There are moments when the glide leg takes a large amount of force while the stride leg is at the end of the push. At this moment, there is considerable opposing force acting on the pelvis, more specifically the pubic symphysis. Getting deep into a single leg squat with a strong isometric force could serve as a way to challenge these tissues at this phase in the stride.

Finding ways to condition the groin muscles to tolerate the force of gliding often leads to arguments among the strength and conditioning specialists of the world. Many leaders in the hockey community completely discount the need for exercises in which both feet are on the ground and instead rely heavily on single-leg exercise. Being a student of the game, I have learned that there are a lot more moments of gliding and turning than there are of pure sprinting. I have found several ways to load the groin in a way that replicates this specific demand. One of the most impactful approaches to tissue prep is the Weck Method bosu elite.

If you made it this far reading and I lost you at “bosu,” I strongly recommend taking an open-minded approach to this wonderful performance tool. Nothing on the gym floor will ever replace the value of knowing your anatomy, but if you are just a coach or athlete looking to bulletproof your groin, be intentional. Focus on adding high-force isometric work to the groin and find several ways to accomplish this. For some ideas check out the link to see how a slide board can become a great training tool for more than just stride work

1. Paajanen H, Hermunen H, Karonen J. Pubic magnetic resonance imaging findings in surgically and conservatively treated athletes with osteitis pubis compared to asymptomatic athletes during heavy training. Am J Sports Med. 2008 Jan;36(1):117-21. doi: 10.1177/0363546507305454. Epub 2007 Aug 16. PMID: 17702996.