Updated analysis of changes in locomotor activities across periods in an international ice hockey game

Brocherie F, Girard O, Millet GP; Biol Sport. 2018; 35(3):261–267

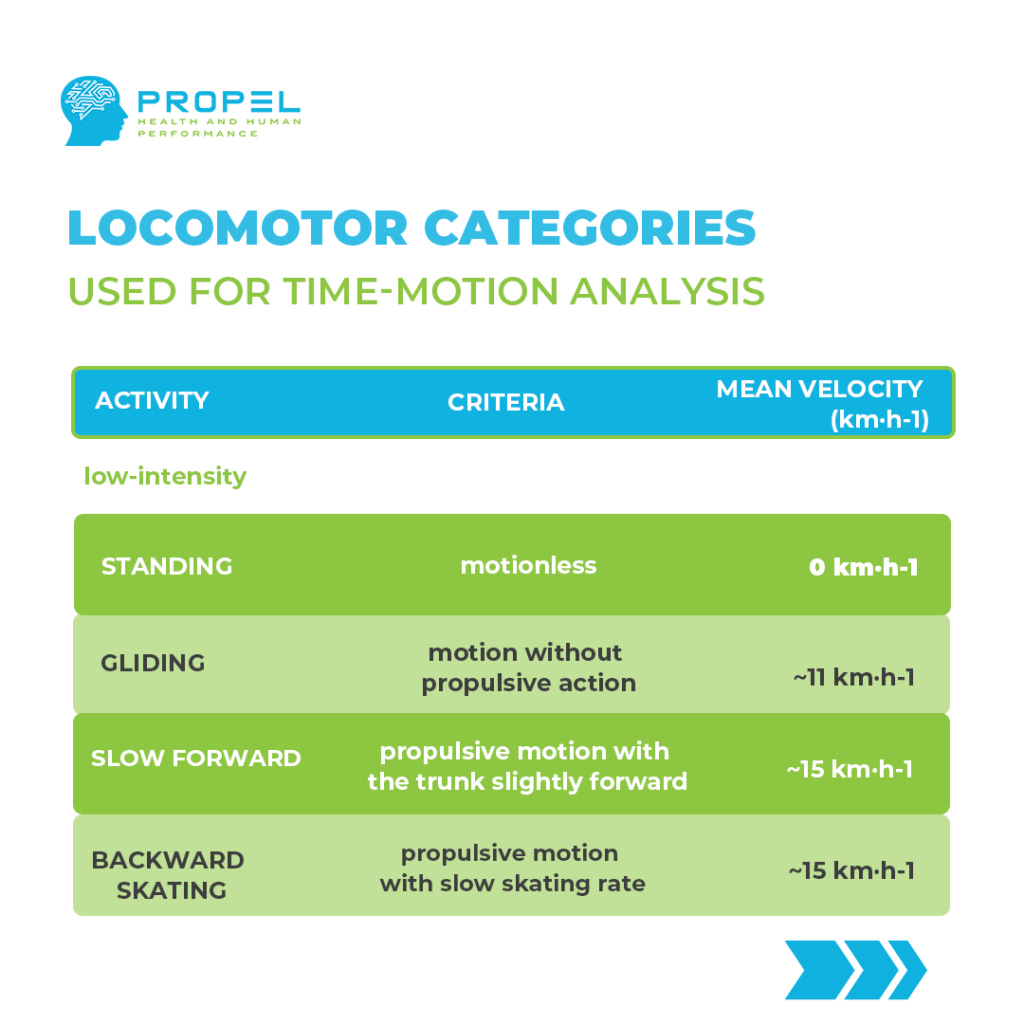

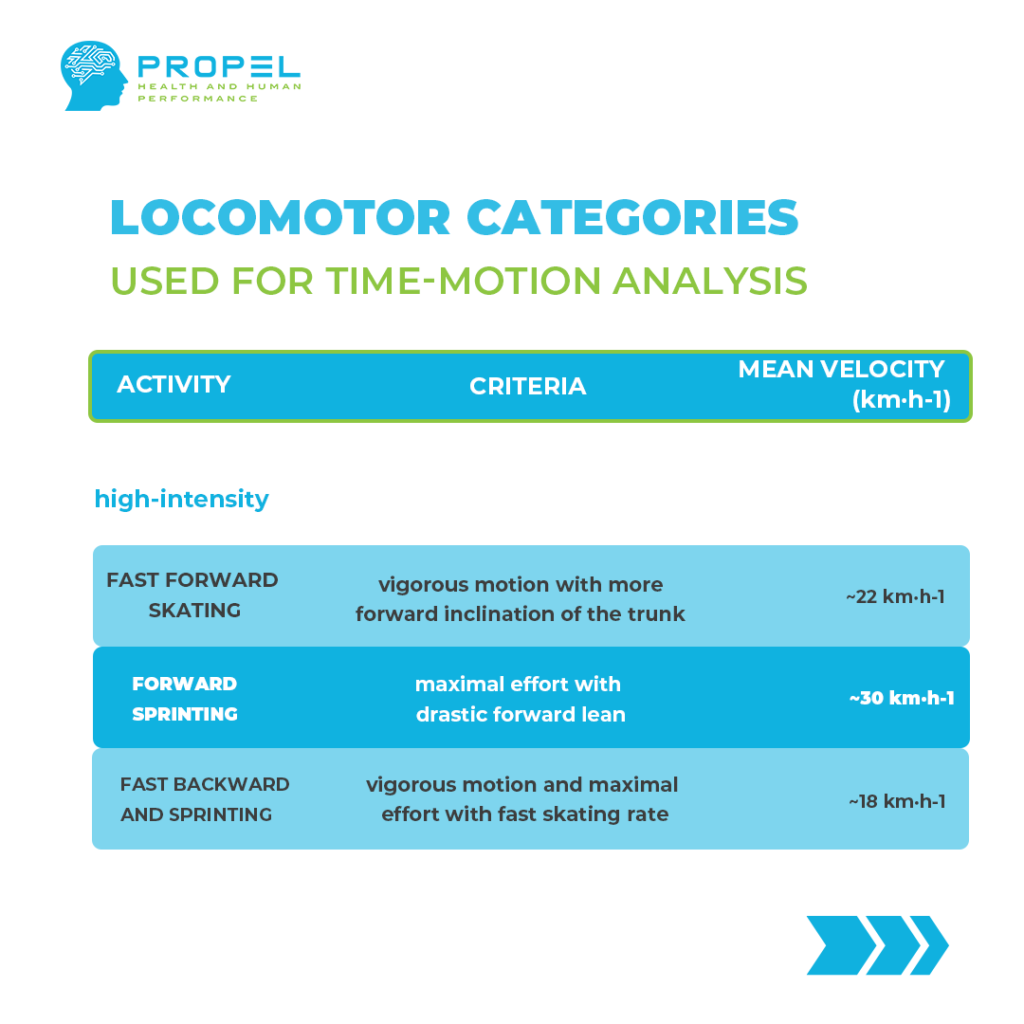

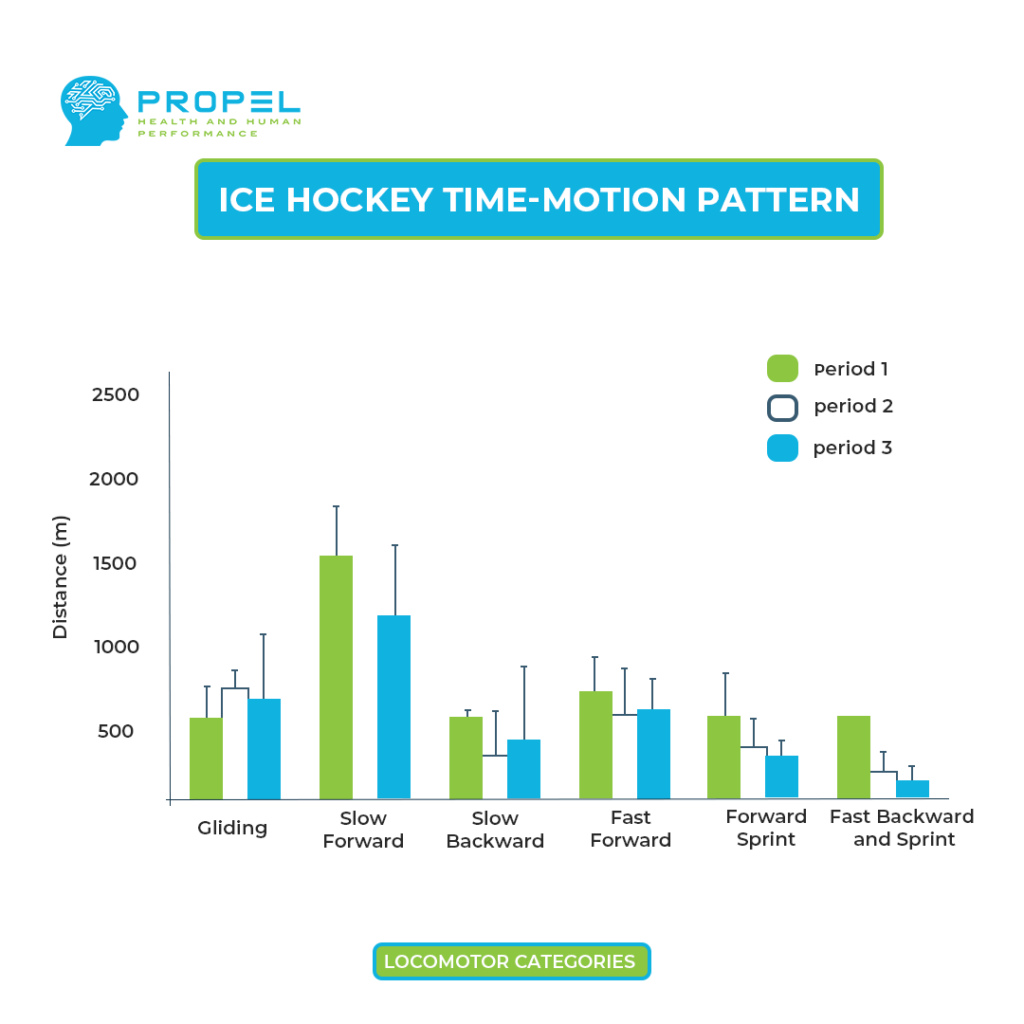

How can we use data like this to our advantage? By understanding the demands of the game we can apply knowledge through the lens of both the rehab and conditioning side of performance. While it is true that hockey is a very fast game, we see time and time again that low-intensity movements play a larger role in the overall activity reported in studies of game. Using time-motion analysis allows researchers to break down each period into its individual movement components and classify them as “high” or “low” intensity based on the speed of the movement. This information leads us to make assumptions about what kind of stress the tissues are under during game play .

The focus of this particular study was monitoring changes in sprint frequency between periods. There were several other data points considered, but the authors paid particular notice to the energy system demands of the game and were able to note a relevant decrease in sprint frequency over the course of the game. Based on this information, we see that the game gets slower as the periods wear on. Players spend more time in low-intensity activities. This would suggest that there is less and less high-stress eccentric loading from sprinting on the adductor tissue each period. With this data, we are led to consider other aspects of the game that might contribute to non-contact groin injury.

My Personal Take:

I have to mention that I live with one foot in the clinic and the other on the gym floor. When I see that less than 18% of the total effective playing time in the study was spent in high intensity movements, I raise an eyebrow. Many clinicians and high-performance coaches alike understand that groin injury is often labeled a non-contact injury. Given the fact that it carries this label of non-contact, we inherently look for a moment in the cycle of the skating stride as the culprit of this non-contact injury. Using this argument, forward sprinting is the moment of highest risk. With the frequency of this injury, however, it is unlikely that we can blame sprinting alone. Groin injury is the fourth most common injury reported in the National Hockey League1.

Non-contact? I am not actually sure this is a legitimate assessment of the injury. It certainly bears a closer look. I have yet to work on a player with groin pain who told me he or she hurt it while sprinting away from a defender on a breakaway. I have, however, heard the story of “my foot got caught…” In this study it was noted that there were five body checks per period with no reduction in frequency from period 1 to 3. In the first period, there were six reported sprints and three in the third period. There was only one shot per period, but this is definitely a high-force moment on the adductor tissue.

How, then, do we explain the high frequency of groin injuries? Maybe it is, in fact, non-contact in nature. Consider the constant postural demand of the groin during all phases of the game. The low friction surface means that stability muscles require various degrees of constant activity. It is an endless cycle of activity to stabilize the pelvis. This endless cycle leads to a very large energy demand. As the author of this study noted, “Muscle lactate accumulation depends on shift duration, and causes metabolic and contractile disturbances that eventually result in decreased ice hockey performance.”

It would seem that lactate accumulation in the groin muscles would be just as significant and, in my opinion, larger than other muscle groups of the lower extremities. This increase in lactate leads to an increased risk for tissue damage. When the relationship between the muscle and the tendon is changed due to a minor pain event, it could lead to degenerative changes in the tendon without changes of muscle function.

As a rehab or reconditioning specialist, what can be done to address the specific tissue demands of the game? We could start by considering some keys for addressing lactate. Here are some factors to consider:

- How do you prepare these tissues for the demand of the game?

- Make sure your rehab or strength program has room for long duration low intensity muscle contractions through combinations of Isometrics and Eccentric lifts

- How do you teach your athletes to eat/drink between periods to give these tissues energy?

- Short term recovery strategies are essential and constantly need to be explored.

- Consider the importance of quick release energy. I like honey for a natural option or some other more synthetic performance products. The key is to find glucose and minimize the fructose for in game fueling.

- Hydration is important and electrolytes will not only help with that aspect of intragame nutrition but assist the stomach in quickly emptying the sugars you eat into the digestive tract.

- How do you promote recovery between events?

- Explore the impact of common recovery tools: Ice/heat/compression/massage. Use what prepares the tissue best for the next event and start by using practice as your chance to explore your options.

- Are there things in the game that may cause overloading of these specific muscles?

- Look at skating technique. Is there something in the stride or change of direction that could be addressed? Using video analysis can be very helpful here.

- Consider common tactical habits that may influence typical tissue-loading environments. Is this the type of player who relies heavily on the physical side of their game or maybe they play a more finesse roll and spend extra time changing directions with and without the puck.

The research on rehab and reconditioning of the groin seems to indicate that it is not a clear road to success and attention must be paid continuously along the way. Looking at studies that monitor in-game demands are a window into tissue preparation strategies.

1. Donaldson L, Li B, Cusimano MD. Economic burden of time lost due to injury in NHL hockey players. Inj Prev. 2014 Oct;20(5):347-9. doi: 10.1136/injuryprev-2013-041016. Epub 2014 Jan 19. PMID: 24446078.